UK vacancies see a new high but households worse off

Topics

UK unemployment dipped to its pre-pandemic rate of 3.8% in the three months to February, but the country’s employment rate remained unchanged at 75.5%, 1.1 percentage points lower than in February 2020.

These figures seem to suggest a strong recovery of the UK labour market, in fact they mask a persistent decline in the labour force participation, with half a million fewer people in work (507,000) and about the same (487,000) more people out of work and not looking than before the pandemic began. The inactivity rate inched up some more in February to 21.4%, driven by people aged 50-64, who report long-term illness or taking early retirement.

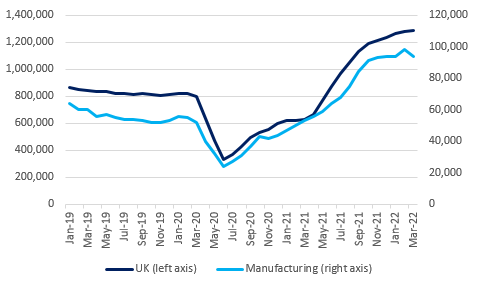

UK vacancies reached a new high in February, of 1.3m. Vacancies in the manufacturing sector fell by 4,000 from its all-time high of 98,000 in January. The sector had 41,000 more vacancies than a year ago, a rise of 79%.

UK and manufacturing vacancies

Source: ONS

Another ONS survey showed that 28% of food and drink businesses (which included manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers) faced labour shortages in March, in line with shortages reported across all UK sectors, at 31%, and with 60% of food and drink businesses reporting a low number of applicants for roles on offer. Naturally, labour shortages drive up wages. In February 2022, 29% of food and beverage businesses reported paying higher wages for existing employees and 30% for new employees compared with normal expectations for this time of year.

In the UK as a whole, wages rose by an average of 4.0% in February, but the ONS warns that the furlough scheme last year implies the current rates of wage growth are pushed up artificially. Rising inflation means that in February, UK workers were 1.0% poorer, not counting the pay growth statistical distortion.

The shift towards worklessness due to sickness and early retirement appears to have become an entrenched feature of the UK economy, which is troublesome in the face of surging demand for workers. Although, as households will cut their discretionary spend due to rises in the cost of living and the disruptions brought on by the war in Ukraine will materialise, businesses will slow down their demand for workers. This, in turn, will mean less pressure for employers to raise wages.

The Bank of England is watching the pace of pay rises carefully as it fears that a tight labour market coupled with high inflation expectations might trigger a wage spiral that would bring a period of prolonged inflation. The bank is expected to raise rates at least two more times this year, following three consecutive rises already. As the conflict in Ukraine means lower growth this year, raising rates might slow down the economy further. This makes the task of bringing inflation under control particularly challenging.