Lowest food inflation since April 2022

Topics

January was the tenth month of food and non-alcoholic drink inflation cooling. Year-on-year prices rose by 7.0%, down from 8.0% in December, the lowest rate since April 2022. On a monthly basis, prices fell by 0.4%.

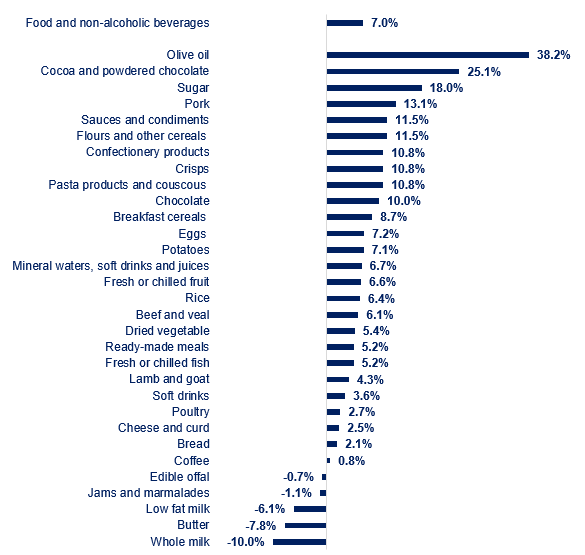

In January, five categories out of the 49 reported by the Office for the National Statistics (ONS) were in deflationary territory, with prices of whole milk and butter dropping at the fastest annual pace of 10.0% and 7.8%, respectively. Inflation slowed for 30 of the remaining categories. Olive oil and ‘cocoa and powdered chocolate’ saw the highest price rises at 38.2% and 25.1%, respectively. These rises are linked to poor harvests, as two consecutive years of droughts in Mediterranean countries have sent olive oil prices to record levels and too much rain in Cote d'Ivoire did the same for cocoa.

Food and non-alcoholic drink year-on-year inflation by category

Source: ONS

On the cost side, manufacturers faced overall costs that were 0.9% lower than a year ago, with UK-sourced ingredients 2.1% cheaper, while imported ingredients still in inflationary territory, albeit the 4.5% rise is a marked slowdown on December’s 7.8% increase. On the month, overall costs fell by 0.5%, the first decline since September 2023. Between October and December 2023, costs rose by 1.6%.

This suggests that some inflationary pressures will persist throughout this year, with some other factors also likely to continue pushing up production costs.

One is wage growth. This April, the National Living Wage (NLW) will increase by 9.8%. This significant increase will impact business costs for both manufacturers and supermarkets, where a large share of the retail labour force is on minimum wage rates. Food and drink manufacturers will see pay differentials squeezed even further between those operating in NLW roles and those operating above entry level roles. All of this comes against a background of generalised wage increases and persistent labour shortages.

Another one is a strong need for investment in the industry. The sharp rise in costs over the last few years caused businesses to postpone or cancel investment projects and divert those funds to day-to-day operations. Over the year to Q3 2023, investment was 33% lower than over the same period in 2019, contrasting with the UK as a whole where investment rose by 5.4%.

Finally, unusual weather might impact certain agricultural harvest in 2024. The El Nino is forecast to continue over the first five months of the year, putting at risk supplies of rice or wheat in the world's leading producers.

At the same time, the steady fall in the prices of global agricultural commodities and energy are acting to dampen inflationary pressures. In January, UN global food prices were 9% lower on the year, with all its sub-indices: meat, dairy, cereals and oils, lower on the year, except sugar, which was 16% more expensive. At the same time, declines in oil prices and UK natural gas in the last couple of months will also curb upward inflationary pressures.

While geopolitics and upcoming domestic regulation introduce further uncertainty for the future path of UK food inflation. The longer the Middle East conflict continues, the higher the potential to negatively impact the cost of oil and energy, which then will influence food prices. Forthcoming domestic regulation, for example ‘Not for EU’ labelling regulation will impose sizeable costs and further deter investment.

The recovery of the industry hinges on its ability to increase investment. Weak food demand renders that recovery quite difficult. December retail food sales were 4.9% lower (in volume terms) than in December 2019. In summary, the economic landscape is still a difficult one for food and drink manufacturers.

In the wider economy, headline CPI inflation held at 4.0% and below market expectations of 4.2%. Core inflation remained steady at 5.1% for a third consecutive month. Core inflation is a better measure of underlying inflation as it excludes excluding more volatile items such as food and energy. While service inflation, another indicator thought to be a better measure of domestic price pressures, inched up to 6.5% from 6.4% in January.

At the same time, pay growth appears to be slowing, with regular wages rising over the three months to December by 6.2%, down from 6.7% over the previous three months and total pay (including bonuses) growth easing to 5.8% down from 6.7%.

All of this leaves the Bank of England in a bind. Financial markets reacted to today’s inflation figures by increasing bets that the Bank might start cutting its rate, currently at 5.25%, in June. At the same time, wage growth might still be too high to reach the 2% inflation target if employers pass wage cost rises through to consumers. And, as inflation is coming down, it’s becoming more difficult for the members of the Monetary Policy Committee to agree on a future course of action for interest rates. At the last February meeting, six members of the Committee voted to keep rates unchanged as they felt key indicators of inflation persistence remained high. In contrast, two members voted for a rise, as they considered wage growth was not consistent with the inflation target, and one member voted for a rate reduction given they saw reduced prospects of entrenched inflation with weak demand outlook and a lengthy time for the impacts of higher interest rates to be felt in the economy.

To support food and drink manufacturers and help hard pressed shoppers, the government must reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens and urgently reassess costly ‘not for EU’ labelling requirements for food sold in Great Britain.