Jobs in the Food and Drink Industry Fall

Topics

Latest data released by ONS shows that 4,000 jobs in food and drink manufacturing were lost in Q3, bringing the total number employed in our industry to 456,000. The number employed has been revised down by ONS and is around 20,000 lower than previous data releases. Employment in the sector had been on an upward trend for a while, but that trend has been now reversed. Jobs, measured by the 4-quarter averages - a better indicator of the underlying trend as seasonality is removed - has been persistently rising since Q1 2021.

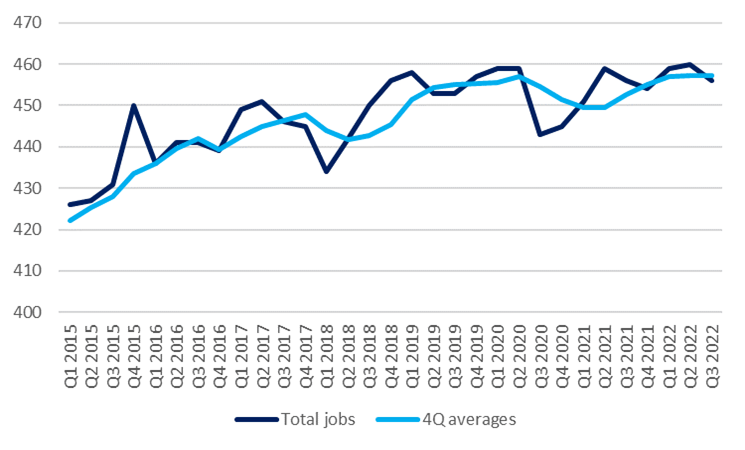

Latest data released by ONS shows that 4,000 jobs in food and drink manufacturing were lost in Q3, bringing the total number employed in our industry to 456,000. The number employed has been revised down by ONS and is around 20,000 lower than previous data releases. Employment in the sector had been on an upward trend for a while, but that trend has been now reversed. Jobs, measured by the 4-quarter averages - a better indicator of the underlying trend as seasonality is removed - has been persistently rising since Q1 2021.

Jobs in the food and drink manufacturing – total and 4-quarter averages (in ‘000)

Source: ONS, JOBS03 and JOBS04 series

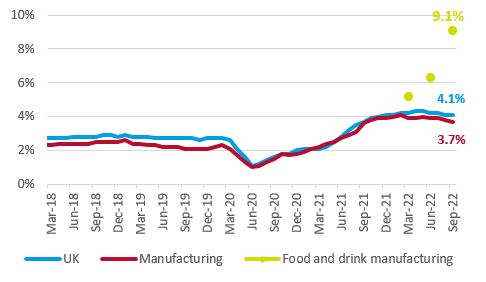

However, in the Q3 State of Industry Survey, food and drink manufacturers reported increased numbers of vacancies. The number of unfilled positions for every 100 jobs has risen to 9.1, up from 6.3 in Q2, and above the UK’s average of 4.1. Even more worryingly, these shortages were reported across a wide range of different roles and skills, from highly skilled engineers to production line workers and drivers.

Vacancy rates in the food and drink manufacturing, UK and manufacturing

Source: ONS and FDF State of Industry Surveys.

The UK labour market remains tight, although there are some signs of cooling. The unemployment rate over the three months to October rose to 3.7%, with employment also rising slightly to 75.6%, now one percentage point below its pre-pandemic level. The inactivity rate -- the proportion of those not working and not actively looking for a job, fell by 0.2 percentage points from the previous three-month period, driven by people retiring who were previously inactive. At the same time, over the three months to November, the number of vacancies fell for the fifth quarter in a row to 1,187,000. However, there are still 391,000 more vacancies than there were pre-pandemic. Despite the fall in the number of vacancies and the rise in unemployment, the number of unemployed people per vacancy remains at a historical low of 1.0.

As the UK economy enters recessionary territory, tightness in the labour market is likely to ease further. The UK finds itself in one of the worst places among developed economies peers. The UK is afflicted by higher interest rates as the Bank of England seeks to cool the economy and drive down high inflation, which is, in part, an aftershock of the pandemic. As is the case for neighbouring countries, the UK is also dealing with a significant energy shock. On top of all this, labour shortages and the impacts of Brexit have added to these serious economic challenges. The UK is the only G7 economy that hasn’t yet recovered to pre-pandemic output levels.

In the short-term, this slowdown might rebalance the labour market without too much pain for workers if firms reduce their demand for labour by mainly removing job announcements, and retaining existing workers. There are signs that households have already reduced spending in real terms, as they seek to manage the cost of living crisis. Real expenditure on food has been in decline for the past four months in both retail and hospitality. The housing market has cooled, with housing prices declining as higher interest rates start to bite, and houses become less affordable homebuyers.

However, the danger for the UK is now a longer-term decline which could see unemployment rising. This is more likely if, falling demand is accompanied by firms reducing investment and output due to rises in interest rates or unmanageable cost pressures. Rising energy expenses is particularly impacting the wider UK manufacturing sector. With gas prices six times above their long-term average, food and drink producers reported a 10-percentage point increase in their energy share of total costs to 22% over the year to Q3 2022. A majority of manufacturers reported that they had paused or cancelled investment projects as a result. In the wider economy, investment fell by 8% in the first half of 2022 compared to H1 2019.

Headline inflation is likely to fall next year with prices set to rise more slowly. The worry is that underlying inflation, driven by wages and non-energy or food goods, seems to be stickier than the Bank of England would like. Markets expect the Bank to raise interest rates again on 15 December. However, with a slowing economy, the Bank’s limited options for 2023 have become particularly scarce.

In short, the next few months will prove extremely challenging for manufacturers and households alike. We would urge the government to take steps to ease pressures faced by the UK’s largest manufacturing sector, food and drink, including supporting businesses to innovate and adapt to the challenging labour market, with SMEs calling for loans to assist their adoption of automation. We would also ask the government to commission an urgent review of the shortage occupation list at all skills levels and make the apprenticeships levy more flexible to build a more secure pipeline of skills for the industry.