Food inflation eases again

Topics

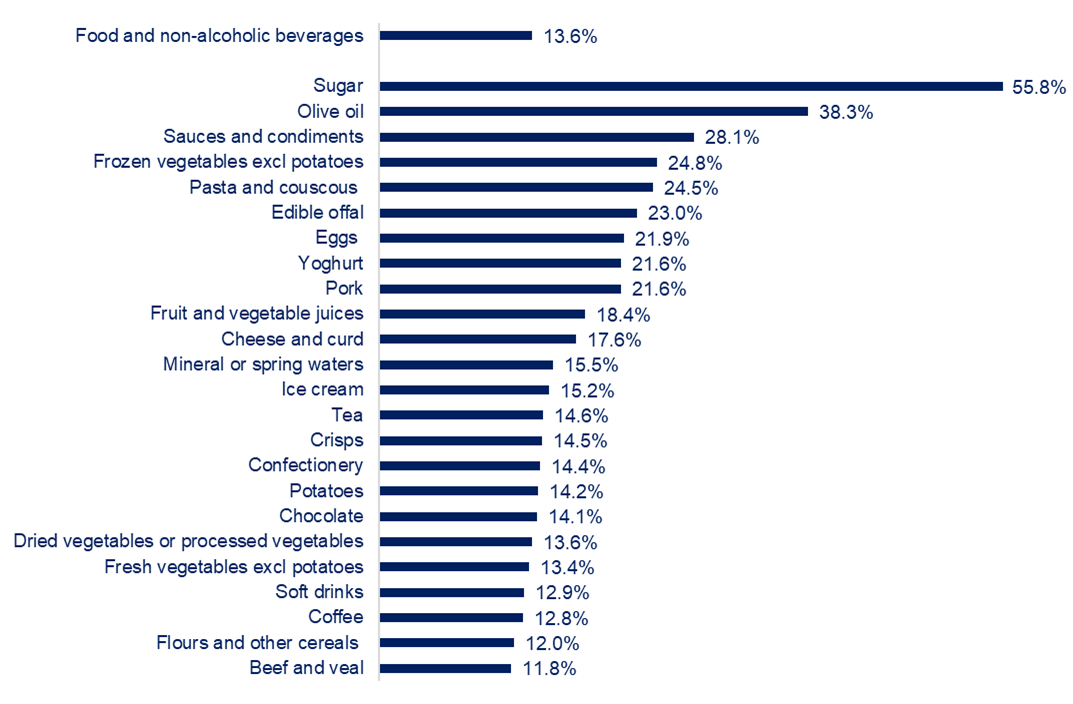

Food and non-alcoholic drink annual inflation eased for a fifth consecutive month in August, to 13.6%, down from 14.9% in July. On the month, prices rose by 0.4%, a faster pace than July’s 0.1% increase.

The easing of inflation is widespread, with 34 out of 49 main food categories reported in the official statistics recording annual inflation in double-digits (down from 40 in July) and 12 for which inflation exceeded 20% (down from 13 in July). Inflation was the highest for sugar, at 55.8% (see chart), and there was deflation for butter, at 3.2%.

Source: ONS

On the producer prices side, Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows that overall costs facing food and drink manufacturers were 2.9% higher in August year-on-year, but that on the month they fell by 0.5%, a fifth consecutive monthly decline.

By category of costs, UK-sourced ingredients saw their third consecutive monthly decline. Annual inflation for the category stood at 0.5%, compared to 0.6% in July. On the month, UK-sourced ingredients were 0.8% cheaper. Imported ingredients continue to see a persistent rise in prices on an annual basis, with 15.1% year-on-year inflation (down from 15.8% in July and monthly inflation at 0.6%). Annual inflation of goods leaving manufacturers’ facilities – output gate prices slowed to 5.2% (down from 6.5% in July and monthly deflation at 0.6%).

Following almost three years of significant cost rises across the board, from ingredients and labour to logistics, transportation, packaging and energy, manufacturers see some cost pressures are now receding. Global agricultural commodity prices have reached a two-year low in August. On average, global food prices were 12% lower compared to last year and 24% lower compared to March 2022, following the Ukraine invasion. However, compared to February 2020, August prices were 22% higher, showing that while many costs have started to decline, they remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels. Any fall in prices typically takes 7-12 months to pass through the supply chain because both purchases of raw materials and sales of finished products are subject to contracts with fixed prices.

Moreover, fresh inflationary pressures are on the horizon. The heat wave in Southern Europe means lower fresh food availability, while the effects of El Niño and the collapse of the Black Sea Grain Initiative could impact global grain supplies.

While the industry continues to struggle with significant labour shortages. Industry’s vacancy rate (the number of vacancies per 100 employees) eased in Q2 to 4.8% from 5.9% in Q1, but labour shortages remain higher than those in wider manufacturing and the UK, of 2.9% and 3.3% respectively. Moreover, labour shortages have been affecting a wide range of roles and skills, from high-skilled workers (project engineers, scientists, IT, sales & marketing), to technical specialists (lab technologists, catering personnel, plant engineering technicians) and production operatives (machine operatives, front line operations, warehouse operatives).

High vacancy rates mean that manufacturers were able to produce less, with repercussions on current revenues and future developments. We estimate that during the year to June (Q3 2022 – Q2 2023), output lost due to labour shortages is £1.4bn, while the loss for Q2 2023 alone is assessed at £192m.

Coupled with squeezed margins, the industry is in a challenging place. Insolvencies continue to rise at a faster pace than in the wider manufacturing sector or GB. In the first half of the year, the industry recorded 161 insolvencies compared to 122 in the whole of 2019. That is 132% more in the first half of the year compared to the whole of 2019, 70% more than in the wider manufacturing sector and 71% more than in the whole economy of Great Britain for the same period.

In the wider economy, CPI annual inflation eased to 6.7% in August, down from 6.8% in July, the lowest since February 2022. The slowdown in core inflation (a measure of underlying inflation that excludes more volatile items such as food and energy) to 6.2% from 6.9% in July was welcome news for monetary policy makers. While still significantly higher than the Bank of England’s 2.0% inflation target, August’s easing might indicate that we are reaching the peak of interest rates.

Pay growth holds strong. In July, regular pay rose by 8.1%, down from 8.2% in June in the private sector and by 6.6% in the public sector, up from 6.2% in June.

However, the UK’s public inflation expectations have been slowing. In August, the British public was anticipating inflation to reach 4.4% in a year’s time. Although higher than the 4.3% the public were expecting when asked in July, it’s reassuring that the public believes that recent high inflation will not persist, as it suggests high inflation has not become embedded in the longer-term economic processes.

It will also help the Bank of England with its decision tomorrow. The Governor of the Bank of England and some Monetary Policy Committee members have signalled that they think a pause in monetary tightening might be appropriate for now. Currently, the bank rate is at 5.25%, a 15-year high following 14 consecutive rounds of increases. While inflation has not yet reached its target, it’s well known that the transmission mechanism of monetary policy (the process whereby higher borrowing costs slowdown the economy and put downward pressure on prices) works with long and uncertain time lags. A pause in interest rate hikes might therefore be sensible, to allow for the outcomes of current rates to manifest.

It's vital that government continues to work with our sector to ensure food and drink price inflation continues to fall, including by reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens. In particular, cumbersome new 'not for EU' labelling plans under the Windsor Framework need a pragmatic alternative if we're to avoid significant, unnecessary costs being placed on already stretched businesses.“