Food inflation surpasses 3%

Annual food and non-alcoholic drink inflation accelerated to 3.3% in January, up from 2.0% in December 2024. This is the highest annual rate since March 2024. On the month, prices rose by 0.9%.

Topics

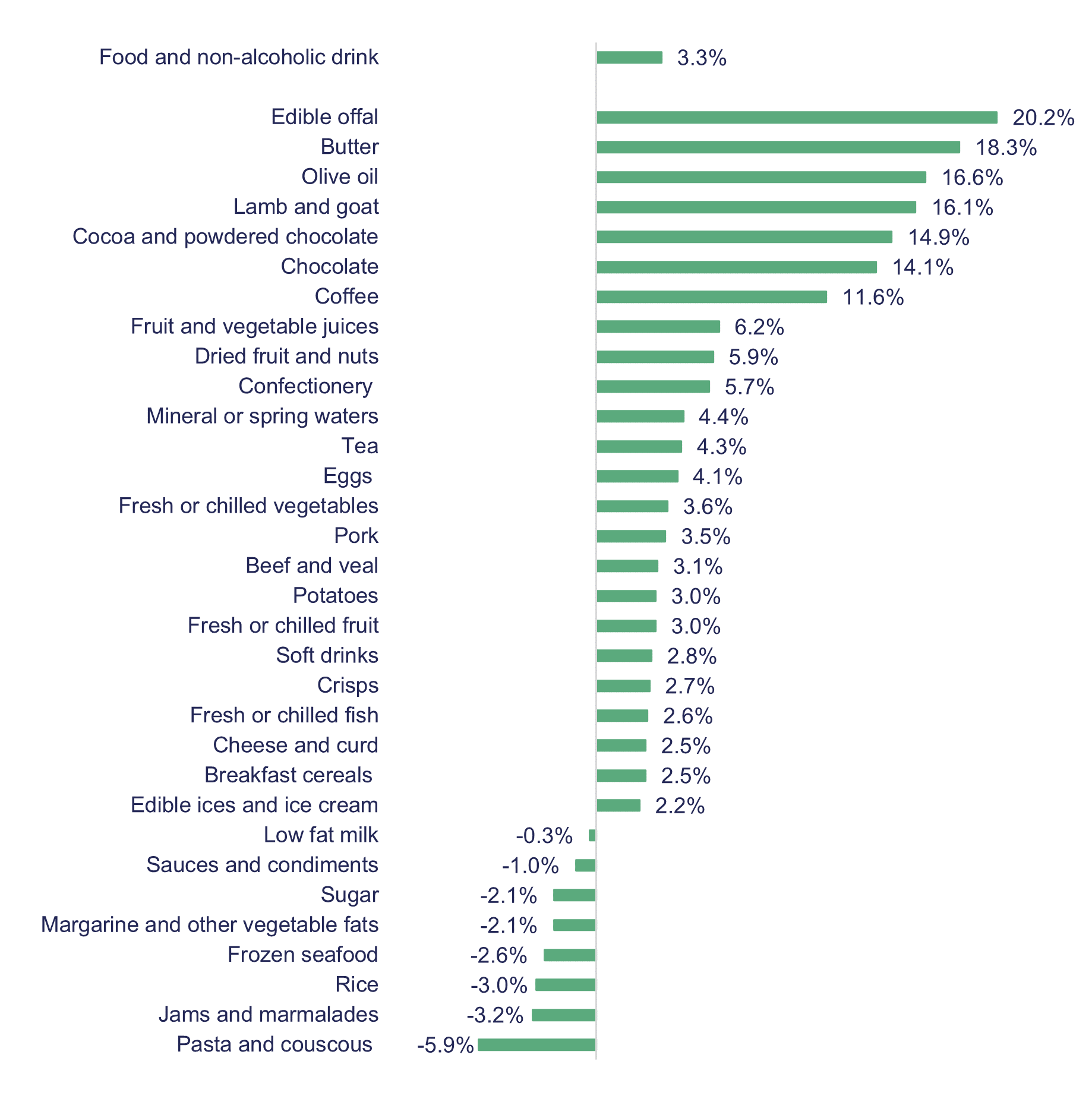

Out of the 48 categories reported in January by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), inflation was below 5.0% for 38 categories, of which 12 were in deflationary territory. Prices fell the fastest for ‘pasta and couscous’ and ‘jams and marmalades’ by 5.9% and 3.2%, respectively, while ‘edible offal’, ‘butter’ and ‘olive oil’ recorded the highest rises at 20.2%, 18.3% and 16.6%, respectively.

Food and non-alcoholic drink year-on-year inflation by category

Source: ONS

Inflation will continue to rise, as inflationary pressures have been building, with utilities (energy and water), agricultural commodities, labour and regulatory requirements all pushing costs up.

Gas prices have seen steady increases during 2024, and electricity prices follow a similar path as gas prices feed onto electricity prices. It’s expected prices will continue to rise through the first half of 2025 due to geopolitical and regulatory uncertainty. There’s continued uncertainty; about the war in Ukraine and its implications for gas supplies to Europe, as well as gas exports from the US. There’s also uncertainty about regulatory changes, such as allowances to fund the Energy-Intensive Industry or a potential extension by Ofgem of the existing Supplier Bad Debt Allowance.

Agricultural commodities are also putting upward pressures on prices. On average, agricultural commodities prices have risen between March and November of last year, although there was a mixed performance amongst different categories. On average, cereals and sugar were 13% cheaper in 2024 than in 2023, while vegetable oils, dairy and meat saw price rises.

A few commodities in particular are impacting manufacturers.

One is cocoa. Global cocoa production has declined for three years, dropping 13% in 2024, causing the worst shortage in 60 years and tripling prices since 2022. Climate change, underinvestment, and tree diseases in West Africa, where 70% of cocoa is produced, are the primary causes. Low prices have historically left farmers without the resources to invest in their crops. Retail chocolate prices are increasing, rising 14.1% in January and are expected to rise further. In the longer term, costs might decrease as farmers use the current high prices to reinvest in their farms and countries outside West Africa, like Ecuador, increase cocoa planting.

Closer to home, butter supplies run very tight. Adverse weather negatively impacted UK production, while global supplies of milk US and New Zealand also ran low. In addition, many producers are electing to sell the cream rather than go to the expense of churning butter. Wholesale butter prices rose for about a year, starting in October 2023, and in January were 60% higher on the year. These significant price movements have trickled onto shop shelves already, with retail butter prices rising for the fourth consecutive month in January, by 20.2%.

In addition, a host of upcoming regulations will also add to manufacturers’ costs. The upcoming rises to the National Insurance Employer’s contributions, the increases in the minimum wage rates, and the upcoming Employment Rights Bill will mean higher labour costs. While EPR, DRS and EU trade measures on imports, specifically health certificates and check rates at the border also bring significant additional burdens.

In summary, food prices will see rises over 2% for the remaining of the year.

All of this happens while manufacturers are yet to make up for losses incurred over the last five years. And comes against a backdrop of generalised weak consumer spend and depressed consumer sentiment.

Retail food sales in volume terms were lower by close to 6% in 2024 compared to 2019, and the cost of living crisis still an issue for many. In December, according to the ONS Survey of Public Opinions and Lifestyle, 32% of adults reported finding it difficult to afford their energy bills, while 30% of those paying rent or mortgage found it difficult to afford those payments. This suggests that the outlook for demand recovery is quite pessimistic. Most of food and drink manufacturing businesses are high volume, low margin businesses. That means that demand recovery is paramount to the health of the sector.

The UK economic prospects are also challenging. The UK economy has narrowly avoided a technical recession in 2024, but the reality is that UK’s economic performance is nothing to write home about. 2025 has started on shaky ground, with depressed business and consumer confidence, a sluggish economy and a worrisome budgetary outlook. The good piece of news is that the Bank of England cut interest rates by 0.25 percentage points to 4.5% in February. Moreover, according to the OBR, the fiscal headroom that existed in October had been wiped out by UK’s debt burden, higher borrowing costs, poor economic data.

Given these circumstances, it's not surprising that many institutions have downgraded their growth forecasts for UK for 2025. The Bank of England, for instance, believes now that the UK will see growth of 0.75% in 2025, down from 1.3% in November.

In a positive scenario, the budget measures coming into effect in April will mean more spending for the economy -in effect, a demand stimulus. A rise in household consumption could provide an uplift to growth in the short run. This would also lift business confidence, which would help investment recover.

An additional contribution to growth in the UK this year is the exchange rate depreciation. This means UK exports are more competitive internationally, so a smaller negative contribution from net exports to GDP growth in 2025.

But, there are many uncertainties. Will the government need to cut spending and/or increase taxes in the spring to abide by its fiscal rules as the fiscal headroom dissipated?

In addition, it’s incredibly difficult to assess what the impact of the global trade restrictions, potential retaliatory measures, and the remaking of the global supply chains into regional ones might mean for the UK economy.

Unfortunately, this month isn’t likely to be a flash in the pan for rising food and drink prices. We’re yet to see the full impact of increasing labour costs, with changes to both National Minimum Wage and National Insurance Contributions coming into force in April, and we expect to see this filter through to shoppers over the coming year. We urge government to work with industry to simplify regulation and bring business costs down to help protect consumers from rising prices.